Stefan Rose, M.D.: Forensic Blood Alcohol Samples Proper Collection Techniques

Life and liberty may be in jeopardy when they depend on the outcome of blood sample testing.

Physicians routinely order peripheral venous blood samples for microbiology culture on sick patients when an infection is in the differential diagnosis of the suspected disease. Microbiology blood cultures are plagued by false positive culture results due to the presence of microbes in the culture that did not originate from the patient’s blood. Those results are called “contaminants”. They may get into the blood culture at any step of the blood collection procedure including from the unclean environment, the patient’s skin, the hands of the person collecting the blood sample, the syringe and needle, and the top of the blood culture bottle.

At least 3,552 publications appear on PubMed for the search term “blood culture contaminants” over the last one hundred years. 1,357 publications appear since 2010. The topic is an important one in medicine. The presence of “contaminates” in the blood culture results often requires repeat testing which delays the correct results as the turnaround time is measured in days. A patient with a life threatening infection may not have days to wait for accurate results. The contamination rate of blood cultures varies across the world and has been reported as high as over 50% in the past and 11% currently in some settings despite everybody in medicine knowing blood culture contamination is a problem and following good practice procedures. The standard that is accepted is about 3% contamination under ideal circumstances.

Blood culture contamination does have increased morbidity and mortality associated with it, so a contaminated blood culture really does put a patient’s life at risk.

Despite our best efforts in medicine, blood culture contamination remains a problem. What is the root cause of the contamination? One generally accepted idea is the following quote from Garcia et al:

“ It is currently accepted that most organisms identified as contaminants in BCs originate from the skin of the patient. Skin, however, cannot be sterilized during antisepsis procedures because approximately 20% of bacteria are imbedded in sweat pores, hair follicles, and other structures within deep layers of the epidermis and dermis.83 It therefore becomes crucial, regardless of the antiseptic used, that it be used in a manner to maximize bacterial kill.”

So, it seems that even with the best trained people and using all the best practices contaminated blood cultures will remain part of the blood collection process.

Contaminated blood cultures may also put a person’s liberty at risk.

Forensic blood alcohol samples should be collected using the same sterile technique as clinical blood culture samples. However the sterile collection of forensic blood samples is never done, so the risk of contamination with microbes is even higher than that of a properly collected medical blood for blood culture sample.

Here is a list of why the forensic blood sample is more likely to be contaminated with microbes:

- The environment is often dirty, say the back of a police car or ambulance.

- The people collecting the blood sample do not have the same level of training and skill as the specialized blood culture collection teams in the patient care setting

- Strict sterile technique is not used including omitting a sterile drape over the site of the venipuncture, omitting sterile gloves worn by the person drawing the blood, inadequate disinfection of the venipuncture site and the blood collection vial is never disinfected prior to needle puncture. When the needle pierces a contaminated blood tube stopper, the needle carries microbes with it into the blood sample tube.

- People experience intermittent episodes of microbes that gain entry into the bloodstream from two major sources within a person’s body. Those two areas are around the face and the large bowel. Trivial trauma like chewing gum and flossing the teeth release microbes into the bloodstream, and pressure on the abdomen (seat belt pressure for instance or other blunt trauma) may release microbes into the bloodstream from the large bowel.

When this occurs it is called transient bacteremia or transient microbemia. If a blood sample is collected after a car crash for instance, the probability is high that the blood sample will be contaminated with microbes from the person the blood sample is collected from.

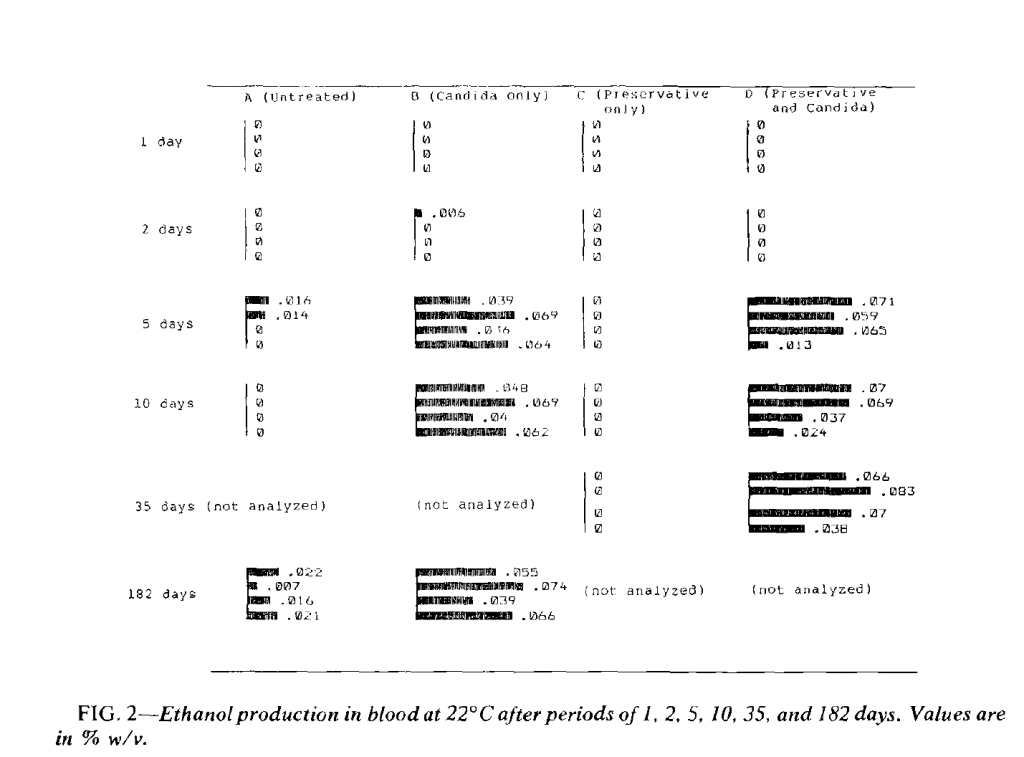

Once the forensic blood sample is contaminated with microbes they may grow in the blood sample and produce ethanol. Fermenting microbes demonstrate an amazing ability to grow under diverse conditions. Cold or hot and in the presence of sodium fluoride fermenting microbes can produce ethanol and falsely elevate a blood ethanol test result.

When this occurs, a defendant may be unfairly prosecuted because the blood sample was not collected in a sterile manner.

References

- Keri K. Hall1* and Jason A. Lyman2, “Updated Review of Blood Culture Contamination”, Clinical Microbiology Reviews, Oct. 2006, p. 788–802

- Reimer et al, “Update on Detection of Bacteremia and Fungemia”, Clinical Microbiology Reviews, July 1997, p. 444–465

- Andreas Kühbacher 1, Anke Burger-Kentischer 1,2 and Steffen Rupp 1,2,*, “Interaction of Candida Species with the Skin”, Microorganisms 2017, 5, 32

- David W. Bates, MD, MSc; Lee Goldman, MD, MPH; Thomas H. Lee, MD, MSc, “Contaminant Blood Cultures and Resource Utilization”, JAMA. 1991;265:365-369

- Kevin A. Davis, MD, “Assessment of Cost, Morbidity, and Mortality Associated with Blood Culture Contamination”, S676 • OFID 2019:6 (Suppl 2) • Poster Abstracts

- Rodney D. Berg, “Bacterial translocation from the gastrointestinal tract”, Trends in Microbiology, Vol 3, No. 4, April 1995

- Joyce Chang, x Ph.D. and S. Elliot Kollman, 2 B.A., “The Effect of Temperature on the Formation of Ethanol by Candida Albicans in Blood”, Journal of Forensic Sciences, JFSCA, Vol. 34, No. 1, Jan. 1989, pp. 105-109.

- Forner L, Larsen T, Kilian M, Holmstrup P. Incidence of bacteremia after chewing, tooth brushing and scaling in individuals with periodontal inflammation. J Clin Periodontal 2006; 33: 401–407.

- Fig 2 below from Chang and Kollman

For more information please contact me at:

Stefan Rose, M.D.

Laboratory Medicine, Forensic Toxicology and Psychiatry

University Medical and Forensic Consultants, LLC.

2740 SW Martin Downs Blvd

Suite 400

Palm City, FL 34990

Phone 561-795-4452

email toxdoc@umfc.com

website www.umfc.com