Stefan Rose, M.D.: Forensic Whole Blood Ethanol versus Hospital Serum Ethanol Tests

Introduction

Ethanol may be measured in a variety of human samples including whole blood, serum, plasma, supernatant, urine, vitreous humor, gastric contents and any other tissue that can be homogenized and dispensed into a sample vial.

For the purpose of this discussion serum, plasma and supernatant will all be referred to as serum unless otherwise noted.

Comparing a serum ethanol result to a whole blood ethanol result is often discussed in forensic cases. Controversy exists in the scientific literature regarding comparison of the two different samples and their corresponding ethanol results. Controversy also exists in civil and criminal cases concerning forensic witness testimony of serum to whole blood ethanol results.

The controversy exists in part because several articles have published experimental results comparing whole blood to serum ethanol concentrations, and forensic chemists and others performing blood ethanol testing often rely upon those published articles. The root cause of the controversy will be explained, and a logical argument provided to explain serum to whole blood ethanol results evidence.

The Sample – Whole Blood, Serum, Plasma and Supernatant

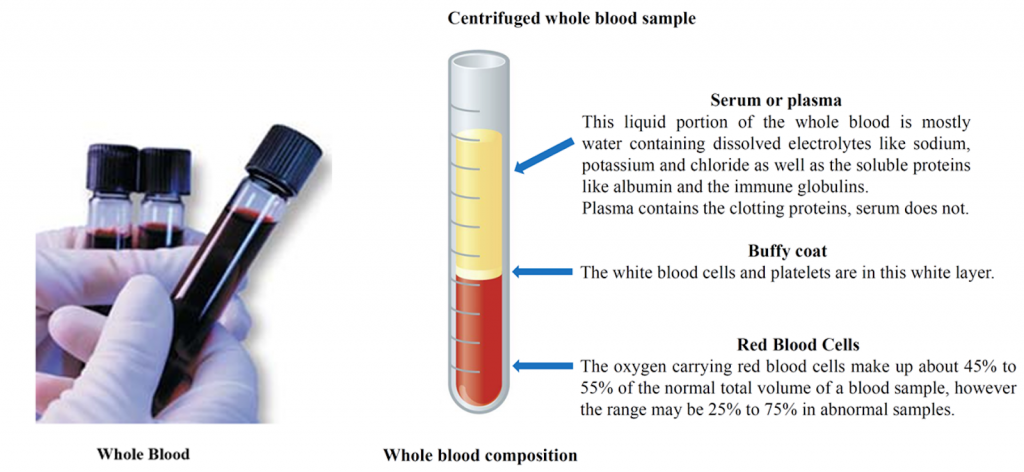

Whole Blood is a human tissue composed of red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets (called the cellular elements) suspended in the liquid portion. The liquid portion is composed of mostly water with dissolved electrolytes, proteins, nutrients and hormones.

(see figure below)

Serum, Plasma and Supernatant

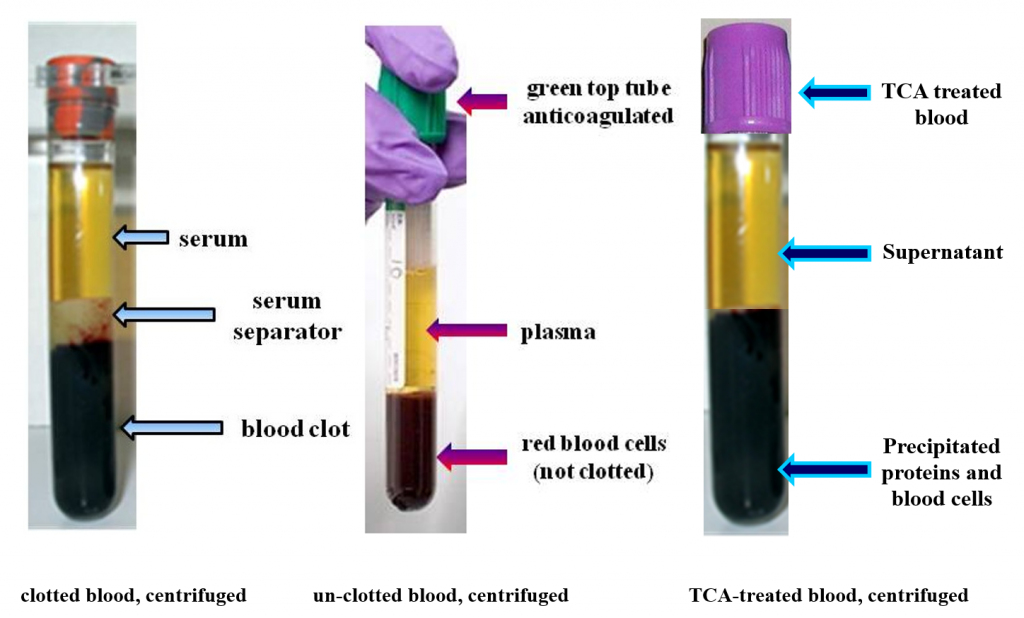

Serum is whole blood that is clotted and then centrifuged. That produces a red blood cell clot at the bottom of the tube with the liquid serum portion above the clot.

Plasma is a whole blood sample that is not clotted and then centrifuged. That produces a mass of red blood cells at the bottom of the tube (not a clot). The liquid portion above the red blood cell mass is called plasma. Plasma contains the clotting factors while serum does not.

Supernatant is un-clotted whole blood treated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The TCA precipitates dissolved proteins out of the liquid solution. After centrifugation the resulting liquid layer is called supernatant.

Serum, plasma, and supernatant are considered equivalent samples for ethanol testing, although strictly speaking they are not the same samples. Serum, plasma and supernatant samples contain more water per unit volume (per milliliter) than does whole blood. The reason for the difference in water content is that serum, plasma and supernatant have more water content per unit volume (milliliter) than red blood cells. Red blood cells contain more protein than water, and ethanol dissolves more into water than protein. The importance of serum, plasma and supernatant containing more water per milliliter is that there is also more ethanol per milliliter compared to whole blood (ethanol dissolves more into water than the protein of the red blood cells).

Getting the Units the Same for Both Samples

Ethanol is measured in (ethanol) weight per (sample) volume. Forensic whole blood results are reported as grams (g) of ethanol per 100 milliliters (usually expressed as deciliter, dl) of blood. Hospital serum ethanol results are reported as milligrams (mg) of ethanol per 100 milliliters (usually expressed as deciliter, dl) of serum.

Since the units grams and milligrams are not the same, the first task is to convert hospital units of milligrams to forensic units of grams. For example, hospital serum ethanol results of 100 milligrams (100 mg) are converted to forensic units of grams (g) by moving the decimal point of the hospital serum result three places to the left.

So 100.0 mg/dl equals 0.100 g/dl.

The unit of volume deciliter (dl) is the same for both samples so nothing is done to that unit. That is all that has to be done for the units conversion.

Converting a Serum Ethanol result to a Whole Blood Ethanol result—the Root Cause of the Controversy

A hospital serum ethanol test result is often directly compared to a forensic whole blood test result. Most witnesses working on a blood ethanol case understand that the two samples are different; however, they often think that the only difference is that serum has predictably higher water content than whole blood. They believe that the serum sample is simply a centrifuged forensic whole blood sample, with all the forensic reliability of a properly collected forensic whole blood sample.

Since serum samples are originally derived from a whole blood sample, the witnesses almost always make the critical judgment mistake of assuming the hospital serum sample has the same forensic reliability as a properly collected forensic whole blood sample.

They also believe that to correct for the difference in water content between the two samples a simple conversion factor may be applied to the serum sample to calculate a forensically reliable whole blood ethanol value.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

As compared to forensic whole blood ethanol testing hospital serum samples are different sample types without a forensic chain of custody collected by differently trained people under different circumstances analyzed with a different analytical method on a different chemistry analyzer.

- Compared to whole blood the water content of the serum sample is higher. Therefore, more ethanol is contained in the serum sample. The higher amount is variable, unpredictable and can range from 10-50% higher than whole blood. In order to equate the serum result to a whole blood result, the serum result has to be lowered with a conversion factor. So, which conversion factor should be used? 10%? 20%? 30%? 40%? 50%? Or some number in between?

- The amount of analytical error allowed in hospital serum ethanol testing is plus or minus 25% (that is right, a total error allowed of 50%).

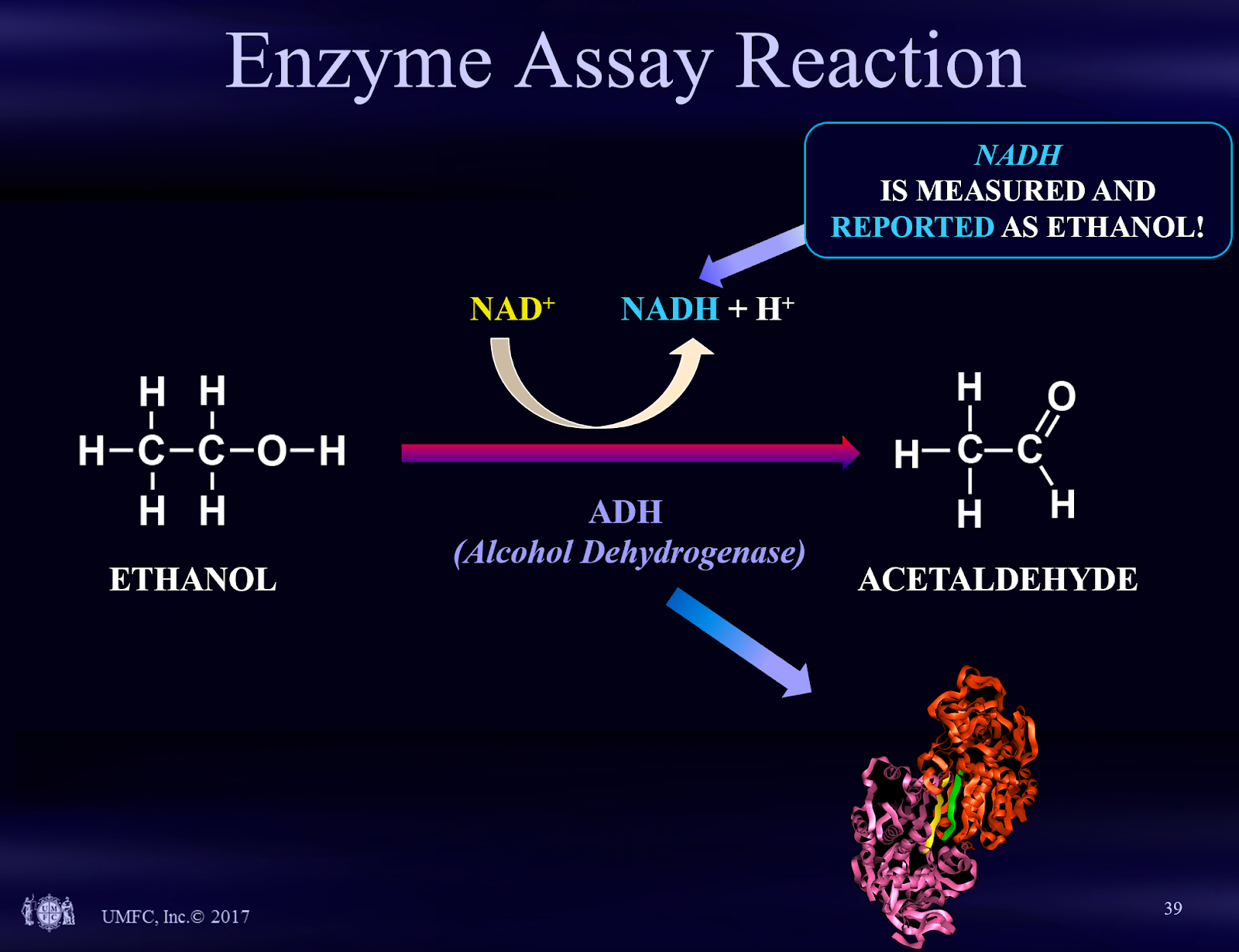

- The hospital serum ethanol testing method does not measure ethanol directly and false positive results may occur. The hospital serum ethanol test is performed by Enzyme Assay as compared to Gas Chromatography-FID, the test method usually performed in the forensic lab.

Enzyme assay is the typical hospital test for ethanol. This test method works by performing a biochemical reaction in the hospital chemistry analyzer. That biochemical reaction produces a compound called NADH. The NADH is measured and is reported out as an ethanol result. This type of test is an indirect test. In comparison, Gas Chromatography-FID is a direct test for ethanol. In forensic science direct tests are preferred over indirect tests because the probability of a false positive result is less with a direct test.

As a result of the above arguments, a hospital serum ethanol test is considered a screening test. Screening tests should be followed by a confirmation test for use in a criminal legal proceeding as the confirmation test has greater reliability compared to the initial screening test. This idea is often stated on the hospital ethanol test report.

Therefore, no single, simple conversion factor can be used to convert a hospital serum ethanol test result to a forensic whole blood result that would have the same forensic trustworthiness as a formal forensic whole blood sample tested in a reliable forensic laboratory.

The graphic below describes the enzyme assay test.

Please contact me if you have any questions about hospital serum ethanol testing.

Stefan Rose, M.D.

Laboratory Medicine, Forensic Toxicology and Psychiatry

University Medical and Forensic Consultants, Inc.

2740 SW Martin Downs Blvd

Suite 400

Palm City, FL 34990

Phone 561-795-4452

email toxdoc@umfc.com

website www.umfc.com

References

- Rainey, P.M., 1993, “Relation between Serum and Whole-Blood Ethanol Concentrations”, Clinical Chemistry, Vol. 39, No. 11, 2288-2292

- Garriott’s Medical Legal Aspects of Alcohol, Sixth Edition

- S.O.F.T. Laboratory Guidelines, 2006